Philosophical and Mystical Approaches to Music and Altered States

by Claudio Vittori

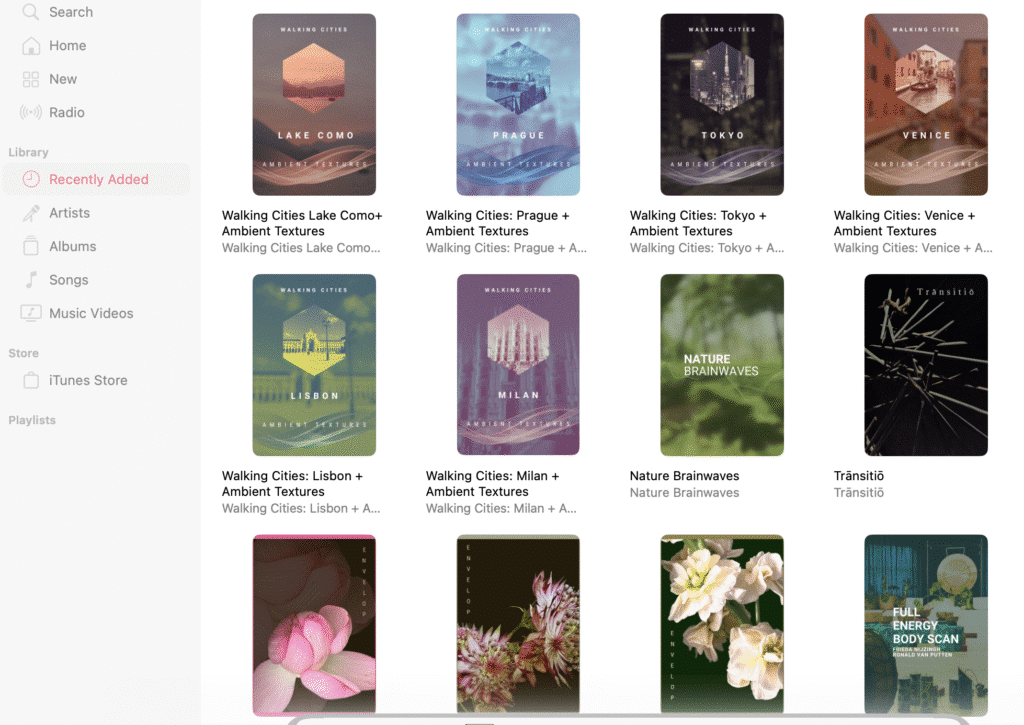

In this second part of the From Ecstasy to Trance series, I explore how ancient philosophy and Islamic mysticism have approached the relationship between music and trance, understood not as a diffuse metaphor but as a structured, relational state of consciousness. I draw from the thought of Plato, Al-Ghazali, and various ethnographic cases discussed by Gilbert Rouget, with occasional reference to Mircea Eliade. My aim is not to describe musical ecstasy as a general experience, but to trace how specific sound practices were coded, feared, or ritualised within systems of meaning and embodiment. I am writing this because, with Flower of Sound and for myself, From Ecstasy to Trance is one of the pillars of our catalogue and a vast source of inspiration. The terms Ecstasy and Trance are often used lightly and with a misguided meaning, and in this series, I want to get into the depths of them.

What is Trance

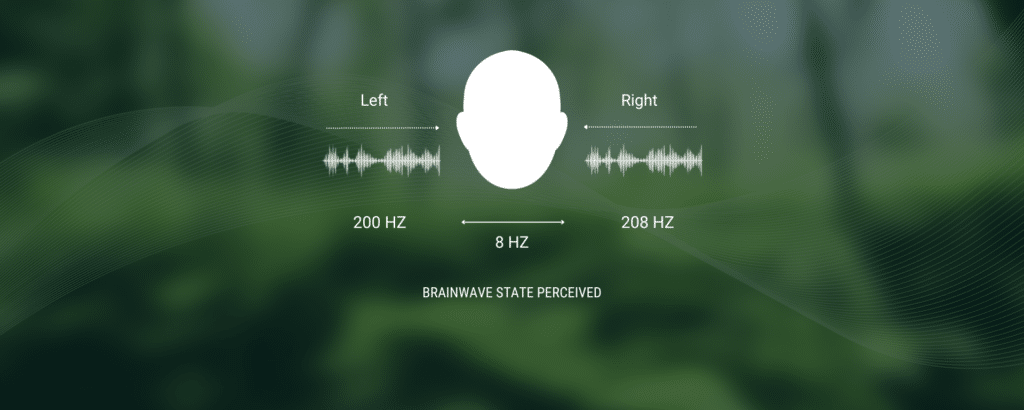

Music has always had the potential to act not only as art, but as a medium of transformation. In contexts of trance, this potential becomes explicit. But what exactly do I mean by “trance”? I’m not referring to metaphorical absorption or aesthetic rapture, but to the culturally framed alteration of perception, often involving rhythmic repetition, bodily activation, and symbolic function.

Following Gilbert Rouget’s fundamental distinction between ecstasy and trance (Rouget, 1985), I focus here on trance as an interactive state, one that requires not only music but a ritual context, an intention, and a relationship. To do so, I look at two radically different but equally rich traditions: the Platonic discourse on musical modes, and the Islamic mystical practice of sama‘ as discussed by Al-Ghazali.

Plato and the Modes: Regulating Sound, Avoiding the Collapse

In The Republic (Book III, 398–403), Plato outlines a detailed ethics of musical modes. The Dorian mode, with its gravity and restraint, was considered suitable for education and inner discipline. The Phrygian mode, by contrast, was viewed with suspicion: emotionally volatile, associated with loss of control, and often connected to rites of Dionysian possession.

The distinction is not only musical. The Phrygian mode, as described by Plato, also carries geographic and symbolic otherness. It is music from “outside”, from Asia Minor, performed by foreign flutists (auletoi αὐληταί, plural of aulētḗs / αὐλητής), and used in cultic practices, the city-state cannot absorb without danger.

Scholars of ancient Greek music continue to debate modal structures, such as whether Dorian was pentatonic and Phrygian diatonic. While some hypotheses point to expressive contrasts based on intervallic content, I do not attribute specific modal structures to Samuel Baud-Bovy, as no verified source confirms he made such claims.

What matters here is not how the modes sound today but what they represented for Plato. The Phrygian mode was not a direct cause of trance but a marker of emotional and ritual disintegration, the affective opening that undermines reason and the polis.

As Rouget notes: “The music of possession does not produce trance because of its sound. It serves as the most visible sign of an identity that breaks from the norm.”

Al-Ghazali and the Voice That Penetrates

Turning to Al-Ghazali, I find a radically different attitude. In his Ihya ‘Ulum al-Din, particularly the Book of Sama‘, Ghazali defends music and recitation in Sufi practice. His focus is not on social regulation, but on internal transformation.

For Ghazali, a beautiful voice reciting words of truth can lead to physical and emotional manifestations—trembling, weeping, and fainting. These are not pathological states but signs of spiritual receptivity.

He writes in the Book of Sama: “A beautiful voice, if it conveys truth and is heard with understanding, is like an enchantment that lifts the veils between the heart and God.”

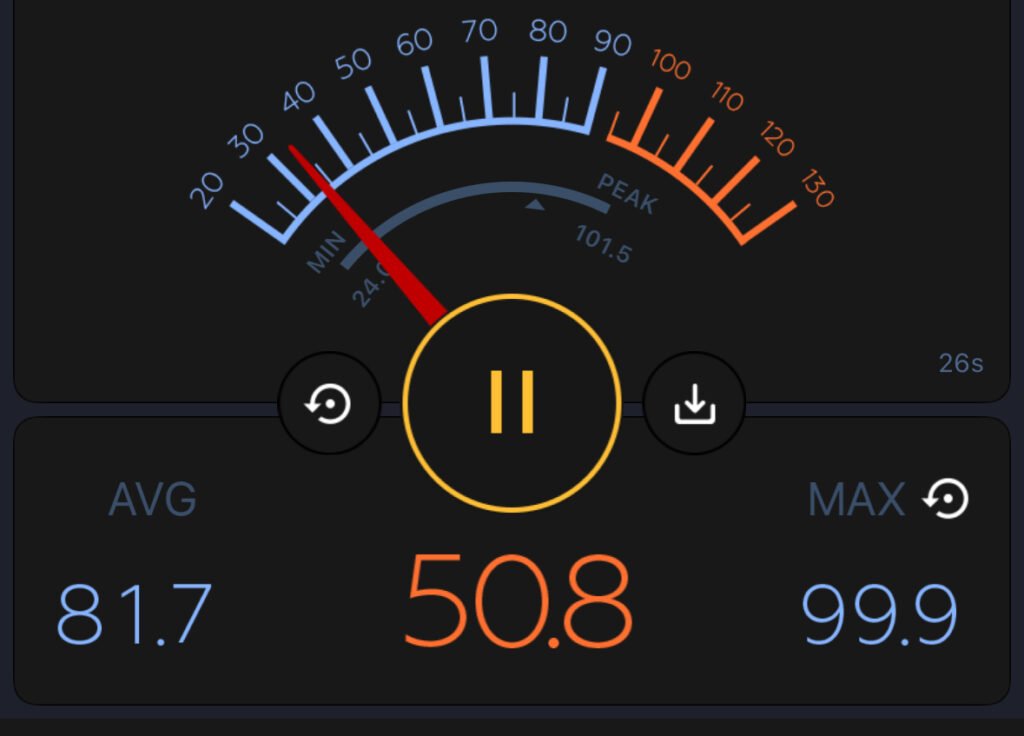

I find his attention to somatic resonance particularly interesting. He points out that when we listen attentively or sing, we can feel vibration in the throat, chest, and abdomen. We can perceive the voice from within. The sound resonates through the body, altering self-perception.

Rouget takes this up in Music and Trance, suggesting that one of the gateways to trance lies precisely in this internalised auditory loop. It is not just hearing, but embodied audition.

Ritual Music and Functional Sound

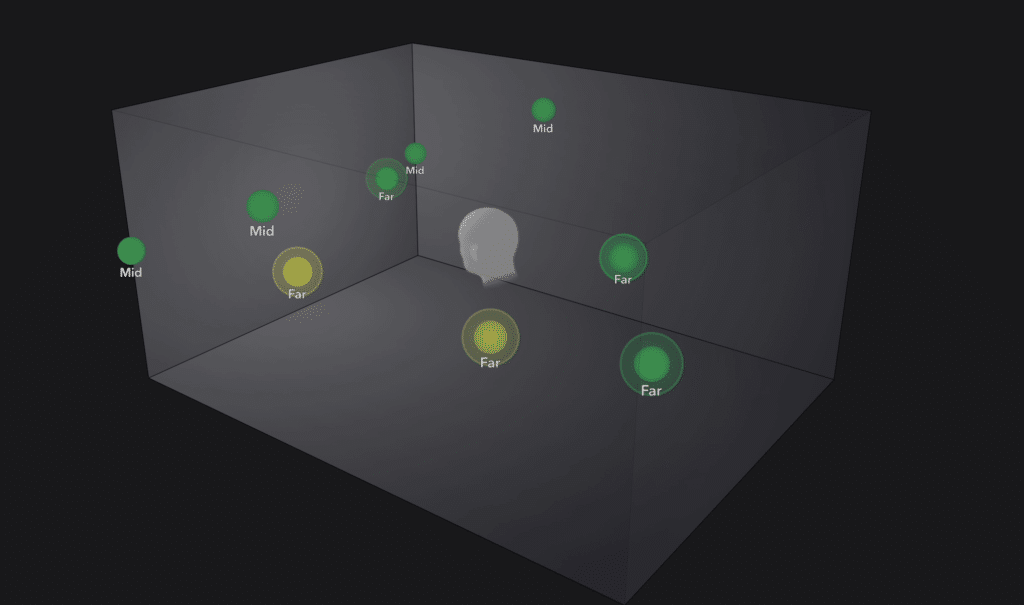

Following Rouget’s line of thought, I avoid the idea that music causes trance. What causes trance is a whole situation: cultural codes, bodily gestures, intentions, symbols. Music becomes effective only when inserted into a ritual logic.

In Jean Rouch’s fieldwork with the Songhai, musical instruments like the one-string fiddle produce low, raspy sounds said to “speak to the spirits.” The music is not beautiful; it is primarily functional and can shift presence.

When you look closer at the Bushmen, healing rituals use song and dance to induce trance in the healer and strengthen social cohesion. Music is an integral part of their lives.

Rouget means this when he insists that: “Trance is never simply the effect of music. It is the product of a relation: between the subject, the sound, and the symbolic context that activates it.”

Music Between Healing and Crisis

The Bible also offers a striking case: David playing the lyre for King Saul. In one episode, the music calms Saul’s anguish; in another, Saul tries to kill David while he plays. Music, here, is not neutral. Camille Combarieu notes that it can be healing or disturbing, depending on what it awakens in the listener. She says, “Music can create pathological states as much as it can restore balance.”

Sound as Situation

What links Plato, Al-Ghazali, and the ethnographers I’ve mentioned is a common intuition: music never acts alone. It becomes meaningful and effective when it enters a symbolic order and speaks through bodies, histories, and ritual frames.

Trance, then, is not the automatic result of sound. It is a situated state activated by the convergence of sound, intention, memory, and gesture. Whether feared or sought after, it reveals how music does not merely reflect a world; it helps construct one.

Missed the first part? Read part 1 here

References

- Al-Ghazali. Ihya’ ‘Ulum al-Din [Revival of the Religious Sciences], Book of Sama‘.

- Camille Combarieu. La musique et la magie. Paris: Félix Alcan, 1909.

- Gilbert Rouget. La Musique et la transe: Esquisse d’une théorie générale des relations de la musique et de la possession. Paris: Gallimard, 1980.— Music and Trance: A Theory of the Relations between Music and Possession. Trans. Brunhilde Biebuyck. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1985.

- Jean Rouch. La religion et la magie Songhay. Paris: Gallimard, 1960.

- Lorna Marshall. The !Kung of Nyae Nyae. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1976.

- Plato. The Republic. Trans. G. M. A. Grube. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing, 1992.

Frequently Asked Questions

Philosophical and Mystical Approaches to Music and Altered States

(From Ecstasy to Trance, Part II by Claudio Vittori)

What is this article about?

This article explores how ancient philosophy and Islamic mysticism understood the relationship between music and trance. Claudio Vittori examines how thinkers like Plato and Al-Ghazali viewed sound, rhythm, and ritual as tools that could shape consciousness and connect the human spirit to the divine.

How does this article define “trance”?

Trance is not treated as a vague metaphor or simple musical rapture. It is described as a structured, relational state of consciousness one that arises through the interaction between sound, body, intention, and ritual context.

What does Plato say about music and trance?

In The Republic, Plato distinguishes musical modes according to their moral and emotional impact. He praises the Dorian mode for its discipline and balance but warns against the Phrygian mode, which he associates with emotional excess and the dissolution of social order.

For Plato, certain musical expressions could threaten the harmony of the individual and the city-state.

What does Al-Ghazali say about music and spiritual experience?

The Islamic philosopher and mystic Al-Ghazali viewed music as a path to divine connection. In his Book of Sama‘, he argued that a beautiful voice reciting truth can move the body and soul (causing trembling, tears, or ecstasy) as signs of spiritual openness, not pathology.

Sound, in this view, is a vehicle of revelation that helps unveil the divine within.

What role does music play in ritual and healing?

Drawing from Gilbert Rouget and ethnographic studies, Vittori emphasizes that music alone does not cause trance. Instead, it becomes powerful when embedded in ritual, symbolism, and social practice.

Among the Songhai and Bushmen, for example, music is used in healing and spirit ceremonies, reinforcing social unity and communication between worlds.

How does the Bible relate to this theme?

The story of David and King Saul illustrates the dual power of music to heal or to disturb. It reflects the idea that music can shift emotional states and reveal hidden tensions in the listener, showing both its therapeutic and destabilizing potential.

What is the central idea of “From Ecstasy to Trance”?

The series argues that music is not just sound it is a situated practice that shapes identity, spirituality, and states of being. “From Ecstasy to Trance” investigates how cultures ritualize sound to induce transformation and explore consciousness beyond ordinary perception.

Why is this topic important to Flower of Sound?

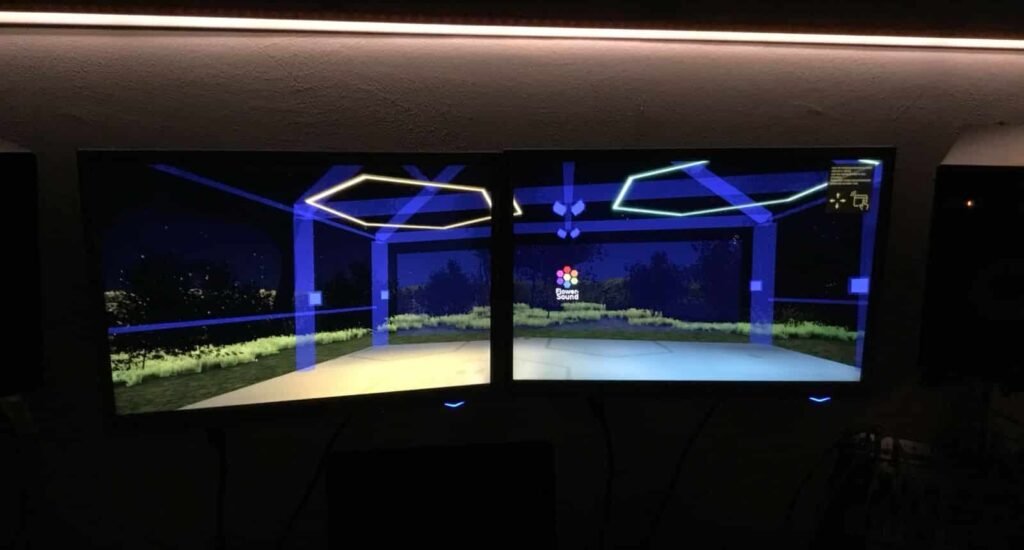

At Flower of Sound, “From Ecstasy to Trance” is one of the core conceptual pillars. The project explores how immersive and spatial sound can lead to well-being, transformation, and expanded awareness, connecting ancient wisdom with contemporary sonic art.

What sources does the article reference?

The text draws from Plato, Al-Ghazali, Gilbert Rouget, Jean Rouch, Camille Combarieu, Lorna Marshall, and Mircea Eliade, combining philosophy, anthropology, and mysticism to illuminate the deep connection between sound and altered states.